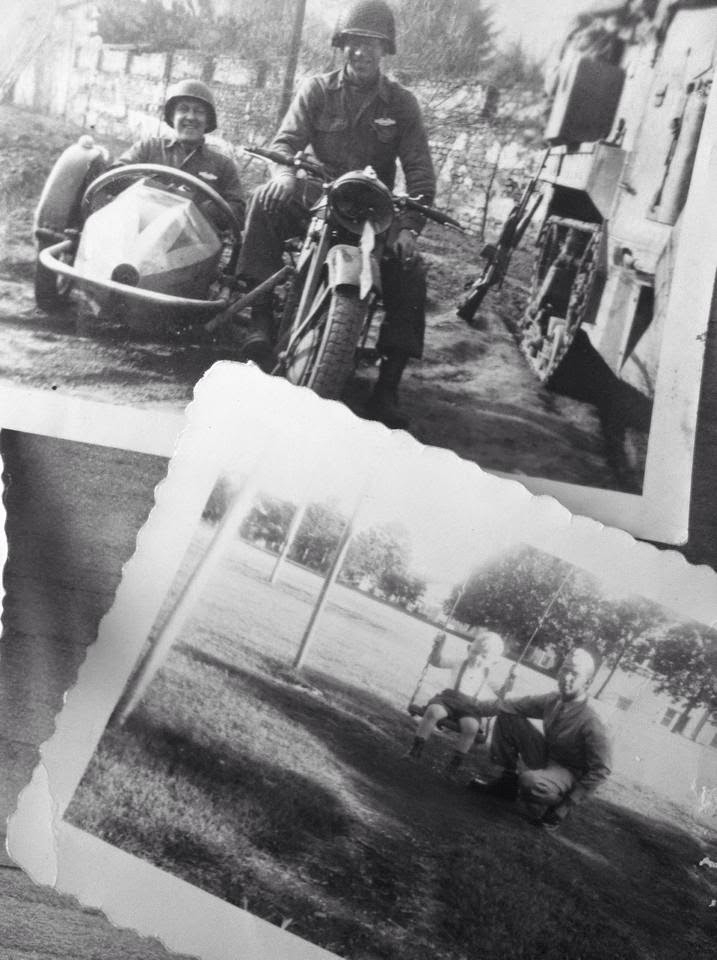

(Photos in illustration are from my own grandfather's personal collection of WW II pictures...)

Robert Smith gives a poignant autobiographical glimpse on the topic of risking much for the sake of conscience in his book A Quaker Book of Wisdom. Quakers, he says, "live to the point," which seemed simple enough to him as a child. As a child, he presumed "religion would provide me with all the guidelines I needed to become the sort of man I hoped to be." But as WW II loomed, his dedication to the Quaker tenet of conscientious objection to war became problematic.

"The Quaker dictate of nonviolence was reinforced through every encounter in my close, warm world. It was a message I had been absorbing all my life--easy to learn and easy to believe. The directive...to love your fellowman and do good. And in 1936 this seemed, without question, to preclude shooting rifles and tossing grenades.

"Eight years later I was a private in an infantry company, marching through the snowy Belgian woods toward the Battle of the Bulge."

All of us eventually find we face that moment where "conscience meets relentless reality." In that place, we must find and express our true faithfulness. For Smith, despite his Quaker upbringing, that meeting of conscience and reality revealed "what was becoming increasingly obvious to me...that Hitler was a brutal murderer who must be opposed, and that fascism was the closest thing to an ocean of darkness that I was likely to encounter in this life."

How did he come to this place of decision? He asked himself and God the hard questions most hesitate to ask: "Is there that of God in every man? Can you maintain that ideal in a world dominated by barbaric cruelty? Does keeping humanity alive take precedence over belief in nonviolence?"

And life experience refined externally what was taking form for him internally.

"One morning a group of us decided to check out the town's bombed-out church. Why did we even bother to go in? As we stepped over, around, and through the debris, we noticed to our surprise that the organ appeared to be intact. A guy said he'd--what the hell--give it a try. Pushing aside a mess of debris, he began to pump the pedals and hit the keys. And some notes began to come out, notes that sounded like Back. And it no longer mattered that everything around was broken, that death was only two days behind us. Here we were, a ragged group of men of differing religious backgrounds who were suddenly embraced by the sensation that something like a divinity was right there with us. Soothing and protecting us. Better than a hot shower or a hot meal. Better than a night without guard duty. It was the sound of eternal life."

In the end, he discovered how best to live his own life's story, with its truths deeply rooted in the soil of a faith-oriented risk for the sake of conscience. "More than half of the draft-eligible Quaker men in the US served in WW II, inspired by the clear moral choices of this conflict. It was a higher percentage than in any previous war. I believe wholeheartedly that the Quakers who were conscientious objectors did the right thing. They were keeping alive a precious ideal--affirming the role of peacemaker and the place of nonviolence in human affairs. Those who went to war did the right thing, too...listening to that still, small voice of God within you, and doing your best to follow the path of truth...No one but God can ever judge the choices we make."

Smith, Robert L. A Quaker Book of Wisdom. New York: Eagle Brook, 1998. pp. 64-77.

No comments:

Post a Comment